This Spring in the Smokies we are witnessing one of nature’s most fascinating synchronized biological events unfold. After 17 years of living underground, Brood XIV (14) periodical cicadas are emerging in massive numbers. It is a spectacular natural event that wildlife enthusiasts and photographers don’t want to miss. It will not occur again until 2042.

Brood XIV: Overview and Distribution

A brood is defined as “a group of cicadas that go through their life cycle together and emerge within a similar area.”2 Brood XIV is considered the 2nd largest periodical cicada brood only being surpassed by Brood XIX. It is actually larger than Brood X (“The Great Eastern Brood”) which emerged in some parts of Tennessee in 2021.1 The current emergence exists in four distinct patches one being “a large, central patch extending from northeast Georgia to southern Ohio”.1 The Smoky Mountains, straddling East Tennessee and Western North Carolina, lie in the heart of Brood XIV territory. Additionally, the National Park provides extensive deciduous forests which are ideal habitat for the cicadas.

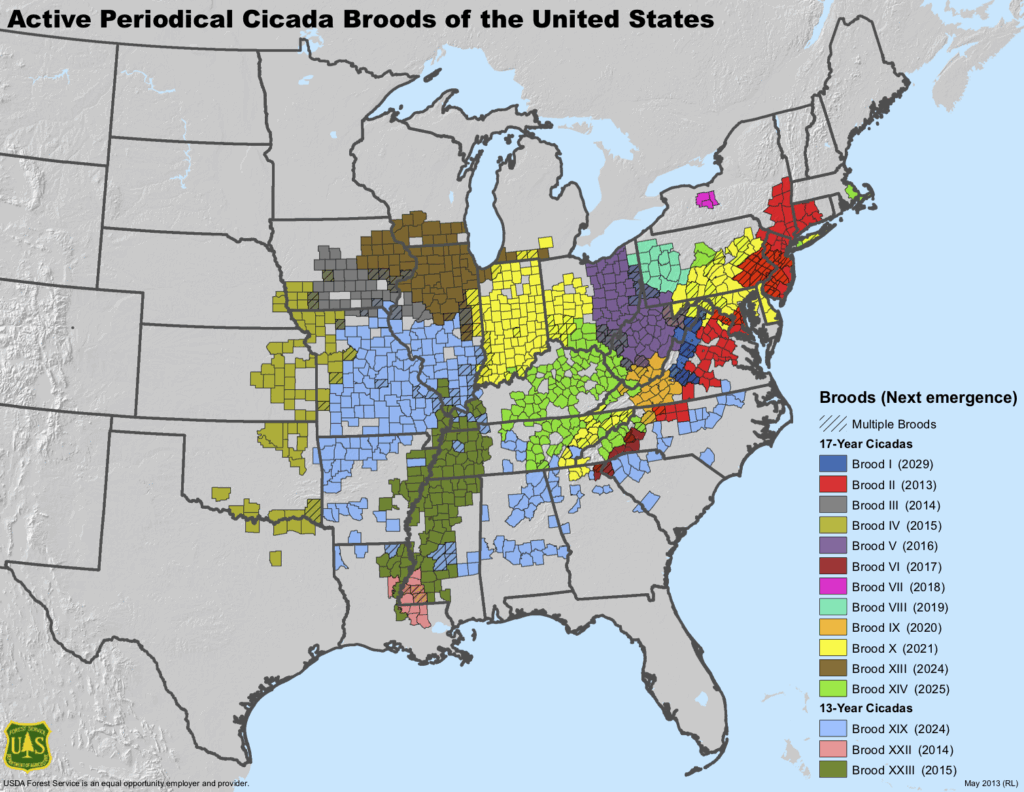

Cicadas are particularly abundant in North America where over 100 species of annual cicada exist as well as the periodical cicada.4 Worldwide there are 3,000 species of cicada. They are found on every continent with the exception of Antarctica.3 Periodical (Magicicada) species are only found in Eastern North America.5 There are 3 species of 17-year Magicicada and 4 species of 13-year. Fifteen broods of periodical cicadas in different stages of their lifecycles exist in the Eastern part of the United States.3

Life Cycle and Biology

The 17-year life cycle of periodical cicadas is among the longest of any known insect. The vast majority of this time is spent in a juvenile form underground, making their brief adult emergence all the more dramatic. Understanding this complex life cycle helps explain the synchronous emergence we’re witnessing in 2025.

After hatching, cicada nymphs drop from the tree canopy and burrow underground where they remain for 17 years6. During this extended subterranean phase, they progress through several juvenile stages. They feed on the sap from tree roots, particularly favoring deciduous trees6. This underground development is remarkably synchronized across the entire brood, allowing for simultaneous emergence nearly two decades later6.

The emergence of the cicadas begins when soil temperature approximately 8 inches beneath the surface reaches about 64 degrees Fahrenheit.5 This typically occurs in late April through May, though warmer regions may experience earlier emergences5. A warm rain often triggers a mass emergence event, bringing millions of nymphs to the surface simultaneously7.

Upon reaching the surface, these nymphs climb nearby vertical structures, including tree trunks, buildings, and other vegetation. There, they undergo their final molt, shedding their exoskeletons to reveal the adult cicada. The abandoned exoskeletons remain attached to these surfaces, creating an unusual visual.

Adult Life and Reproduction

The adult stage of the cicada’s life is relatively brief compared to its lengthy underground development. Once emerged, male cicadas begin producing their distinctive buzzing sound-described by some as “alien-like”-to attract females5. This chorus can reach remarkable volume levels when millions of cicadas are present, creating one of the most distinctive soundscapes in American forests. Luckily, they always sing during the day not at night8. Click here to listen to a cicada singing.

Following mating, females cut slits in small tree branches using a specialized organ called an ovipositor, where they deposit their eggs5. When the eggs hatch in mid-summer, the tiny nymphs fall to the ground and quickly burrow underground, beginning the cycle anew5. Most adult cicadas live only a few weeks, though the emergence period in a given area typically lasts 4-6 weeks due to the somewhat staggered nature of the emergence5.

Ecological Significance

The mass emergence of periodical cicadas creates a significant pulse of biomass in forest ecosystems, with wide-ranging ecological implications. Their presence affects everything from predator populations to forest regeneration.

Predator Relationships

The synchronous emergence of millions of cicadas represents a strategy called predator satiation. By emerging simultaneously in overwhelming numbers, cicadas ensure that predators cannot possibly consume all individuals, allowing many to survive long enough to reproduce. An example of predator satiation in the plant world is an acorn mast. This phenomenon creates a temporary abundance of food for various forest predators, including birds, mammals, reptiles, and other insects.5

In the Great Smoky Mountains, this abundance benefits numerous native species. Birds particularly take advantage of this bounty, with species from thrushes to woodpeckers to migratory warblers, feasting on the protein-rich insects. Bears and other mammals experience a caloric windfall during emergence. Even predators that don’t typically consume insects may opportunistically feed on cicadas during peak emergence. Click here to see a squirrel consuming cicadas.

Impact on Forest Ecosystems

Beyond serving as prey, cicadas impact forest ecosystems in several ways. Their emergence from the ground creates countless small tunnels, aerating the soil and improving water penetration. The adult cicadas’ egg-laying behavior can sometimes cause the death of branch tips due to the slits cut by female cicadas. While this may temporarily impact individual trees, it acts as a natural pruning mechanism and rarely causes significant harm to mature trees.9 Additionally, the mass die-off of adult cicadas provides a nutrient pulse to forest ecosystems. As cicada bodies decompose, they release nitrogen and other nutrients that fertilize the forest floor, potentially benefitting plant growth in the following seasons.

Conclusion

The 2025 emergence of Brood XIV periodical cicadas in the Great Smoky Mountains represents a remarkable biological event and an extraordinary opportunity for nature enthusiasts and photographers. The synchronized appearance of these long-lived insects offers a window into one of North America’s most distinctive natural phenomena. With their complex life cycle and ecological significance, these cicadas embody the intricate relationships and timing that characterize forest ecosystems.

For visitors to the Great Smoky Mountains during this special season, the experience of witnessing millions of cicadas completing their 17-year journey provides both memorable encounters and deeper appreciation for the cyclical nature of life. The photographs and observations gathered during this emergence will document a biological event that won’t recur until 2042.

Elevate Your Photography with Spruce Photo Tours

The Great Smoky Mountains offer a premier stage for photographing landscapes and wildlife, and Barry Spruce provides the expertise to make it happen. Our workshops offer a small group experience; while private guided tours offer one-on-one photography instruction. Whether you seek a multi-day workshop or a tailored private tour, our approach ensures personalized instruction and an unforgettable time exploring the Smoky Mountains. Reserve your spot today at SprucePhotoTours.com, and join us to explore, experience, and photograph!

References:

- University of Connecticut, Biodiversity Research Collection, Periodical Cicada Information Pages, “Brood XIV”, https://cicadas.uconn.edu/broods/brood_14/

- Quigley, Tyler and Deviche, Sabina , Arizona State University, Ask A Biologist, “Rising Cicadas”, https://askabiologist.asu.edu/periodic-cicadas

- Quigley, Tyler and Deviche, Sabina, Arizona State University, Ask A Biologist, “Rising Cicadas”, https://askabiologist.asu.edu/explore/cicadas

- National Park Service, “I Didn’t Know That!: Emerging Cicadas”, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/idkt_cicadas.htm

- University of Connecticut, Biodiversity Research Collection, Periodical Cicada Information Pages, “General Periodical Cicada Information”, https://cicadas.uconn.edu/general_information

- Gulker, Matthew, University of Michigan, Museum of Zoology, Animal Diversity Web, “Magicicada septendecim, Linnaeus’ 17-year cicada”, https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/magicicada_septendecim/

- Cicada Mania, “Brood XIV (14) Cicadas will emerge in 2025 in twelve states”, https://www.cicadamania.com/cicadas/periodical-cicada-brood-xiv-14-will-emerge-in-2025-in-thirteen-states/

- Rosenholm, Glenn, USDA Forest Service, Eastern Region, “Here Come the cicadas!”, April 29, 2024, https://fs.usda.gov/about-agency/features/here-come-cicadas/

- EPA, “Cicadas”, https://www.epa.gov/safepestcontrol/cicadas